| Go Back: Module 18: "Leveling Up" Your Instruction | You Are Here: Module 19: Student Voice & Agency | Next: Module 20: Talking About Race with Youth |

After working through this module, you will be able to:

- Define youth voice and youth agency.

- Explain the connection between voice, agency, and youth development.

- Act in your library to provide opportunities for BIYOC to develop and express their voices.

Introduction

When students are allowed to speak and to write their truth, they begin the process of introspection, inquiry, and critical thinking.

–Jyothi Bathina, PhD

The concepts of voice and agency are critical to developing inclusive library programs and services where BIYOC can develop and thrive. Providing opportunities for BIYOC to share their personal narratives, to express their ideas and their opinions, and to speak and write their truths legitimizes their lived experiences, celebrates their culture, and encourages them to use their voices for personal, civic, and political reasons. As we’ll discuss below, when adults work with BIYOC to develop their voices and agency, BIYOC strengthen their academic skills and competencies, develop their leadership abilities, build strong relationships with adults, and feel empowered to use their voices to effect change.

Defining voice & Agency

What do we mean by “voice”? The best way to understand it is to see it in action. Here are four examples of youth using their voices to speak out and to effect change in their communities.

As an 11-year old, Marley Dias was frustrated at the lack of books that showed characters like her. She decided to start a campaign that collected books with Black girls as the main characters. Not only has she collected over 9000 books which she has donated to communities, but she has also developed the 1000 Black Girl Books Resource Guide to help youth, educators, and librarians find those books. After the creation of the resource, she toured the country to speak to educators, legislators and others about how to increase the pipeline of diverse books. She is currently a student at Harvard University.

In this video, fourth-grade students in Ms. Nwoye’s class at Stedwick Elementary School in Montgomery County, Maryland speak out against racism and the harmful impact it has on youth.

In this video produced by SheKnows Media’s Hatch program, teens from different ethnic and racial communities speak out about microaggressions and their impact on teens’ self-esteem.

Following the school shooting in Parkland, Florida youth across the country engaged in protests and walk-outs to make their voices heard about gun violence. In this video, filmed at a rally for gun control in Raleigh, North Carolina, two high school students share a powerful spoken-word piece they wrote.

As these four examples demonstrate, youth voice has two dimensions. One dimension recognizes that BIYOC have stories to tell, that their stories are important, and that by telling their stories they enrich the narrative about what it means to be a BIYOC in the United States today. The second dimension includes a social action component – one that recognizes that youth can provide a unique insight into the issues facing BIYOC and their communities. This dimension supports youth agency and positions youth as agents of change in their schools and communities.

For BIYOC, agency can include:

- Participating in collection development, policy, and programming decisions.

- Influencing class topics, activities, and final products.

- Sharing their ideas about problems that exist in their schools, libraries, and communities and offering potential solutions.

- Collaborating with other youth and with adults to engage in Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR).

Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) is a research method in which youth who identify as BIPOC who are directly impacted by a problem engage as co-researchers in the research process. In collaboration with adults, BIYOC (1) identify an issue that is affecting their own education, library, or community; (2) determine how to best study the issue; (3) conduct the research; and (4) develop and enact solutions that affect change. For more information, see the YPAR Hub website.

REspond

REspond

In your journal, brainstorm a list of issues that are important to BIYOC in your school, library or community – issues they care about and that impact their lives. To make your list more inclusive and authentic, think about ways to get input from the youth you work with. Possible ideas include surveys or questionnaires, focus groups or forums, graffiti boards, or direct conversation (if you have a trusting relationship).

images of practice

images of practice

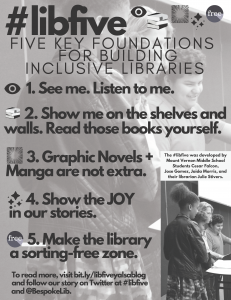

In this Image of Practice, learn how school librarian Julie Stivers worked with three of her eighth-grade students at Mount Vernon Middle School in Raleigh, North Carolina to develop student-led professional development for librarians on how to create equitable and inclusive libraries. Over the course of several months students Jaida Morris, Cesar Falcon, and Jose Gomez engaged in YPAR. They began by reading academic research that directly related to the topic and then embarked on their own action-based research. Based on their research, they developed The #LibFive: Five Key Foundations for Building Inclusive Libraries. Watch this video to hear from Jaida, Cesar, and Jose about the process and the #LibFive concepts.

Why Is It Important to Cultivate Voice and Agency?

The soul of a people lives in that people’s voices and is streamed in the continuous sounds that run deep like rivers through their lineage.

– David Kirkland

As this quote from David Kirkland captures, voice matters! Libraries must be spaces where BIYOC are encouraged to develop their voices, to tell their stories, and to share their perspectives on how we can work together to create a just and equitable society.

Research also shows that cultivating voice and agency affects youth development positively. Efforts to increase voice and agency make a difference in the attitudes, behaviors, and engagement of all youth. Did you know:

- Studies have found that youth improved academically when teachers constructed their classrooms in ways that valued youth voices (Mitra, 2004; Oldfather, 1995; Rudduck & Flutter, 2000).

- Increasing student voices in schools helps to reengage alienated youth, provide them with a strong sense of their abilities, and build their awareness that they can make change (Oldfather, 1995).

- Students report valuing their schools and their education more when their teachers heard their voices and honored them (Mitra, 2004).

- Increasing student voice improves students’ understanding of how they learn (Johnston & Nicholls, 1995; Mitra, 2004).

- Agency can act as a source of social capital for BIPOC, leading to further educational, employment, and enrichment opportunities (Mitra, 2004).

- Youth voice initiatives give BIYOC a platform to assert their identities as intelligent young people who have much to offer the world – identities that are often suppressed in schools.

- Youth voice initiatives provide a context for literacy learning – one that allows BIYOC to develop and utilize multiple literacies.

- Youth voice initiatives, especially YPAR, helps BIYOC learn academic language, build leadership skills, gain confidence, and develop a sense of social responsibility (Morrell, 2004, 2006).

- The development of youth voice instills in BIYOC the belief that they can transform themselves and institutions (Mitra, 2004).

What Does Cultivating Voice and Agency Look Like?

Often it’s difficult for librarians and educators to imagine what cultivating voice and agency might look like. In Module 18, we talked about “leveling up” with Dr. Bank’s Framework. Level 3 and Level 4 of the framework provide natural opportunities for educators and library staff to amplify youth voice and to create units or programs that allow youth to act in their communities, whether the community is the classroom, school, library, or beyond.

Providing opportunities for BIYOC to engage in counterstorytelling is another powerful way to cultivate voice and agency. Counterstorytelling is “a method of telling the stories of those people whose stories are often not told,” especially those who do not belong to the dominant white, cis, heterosexual, able-bodied culture (Solorzano & Yosso, 2002, p. 26). Counterstorytelling not only ensures that the voices of BIYOC and other marginalized youth are heard, but it also validates their life experiences, provides a venue for them to share their own narratives and community wealth, and serves as a powerful way to challenge and subvert the versions of reality held by the privileged. Richard Delgado (1989), who introduced the concept, outlines a number of ways that counterstorytelling benefits groups that have been traditionally marginalized and oppressed in the United States. By telling (and hearing) counterstories, BIYOC:

- Gain healing by understanding the historic oppression and persecution their community has faced,

- Realize that other members of their community have similar feelings and experiences and that they are not alone,

- No longer blame themselves or their community for being marginalized, and

- Construct additional narratives to challenge the dominant narrative (Delgado, 1989, p. 2437).

Members of the dominant culture also benefit from hearing counterstories. Delgado (1989) argues that counterstories and help them overcome their “ethnocentrism and the unthinking conviction that [their] way of seeing the world is the only one – that the way things are is inevitable, natural, just, and best” (p. 2439).

For BIYOC, counterstories provide the mirrors that Rudine Sims Bishop refers to in her seminal work “Mirrors, Windows, and Sliding Glass Doors.” For youth who belong to the dominant culture, they serve as windows. For both, they can act as sliding glass doors. Bishop (1990) writes:

Books are sometimes windows, offering views of worlds that may be real or imagined, familiar or strange.

These windows are also sliding glass doors, and readers have only to walk through in imagination to become part of whatever world has been created or recreated by the author.

When lighting conditions are just right, however, a window can also be a mirror.

Literature transforms human experience and reflects it back to us, and in that reflection we can see our own lives and experiences as part of the larger human experience. Reading, then, becomes a means of self-affirmation, and readers often seek their mirrors in books.

In Modules 24a and 24b, we will discuss #OwnVoices children’s and young adult literature – a form of counterstorytelling – but we can also engage BIYOC in telling their own counterstories as a way of cultivating voice and agency. The videos you watched at the beginning of this module, including the Lib Five image of practice, are examples of counterstorytelling. In these videos, youth are speaking their truths and sharing their experiences. The documentary When Your Hands Are Tied that you watched in Module 9 is another example of counterstorytelling in action. In this documentary, Native youth counter the dominant narrative about Indigenous people in the United States, share their cultural wealth, and demonstrate how they are expressing themselves in the contemporary world while maintaining strong traditional lives.

Respond

Respond

In your journal, brainstorm a list of ways library staff can work with BIYOC to create their own counterstories and share them with their peers and the broader community. In addition to traditional storytelling methods, consider how you might use digital storytelling tools. AASL creates a list of the best websites for teaching and learning that contains links to recommended digital storytelling tools, many of which are free.

What is Co-Design?

Co-design is the practice of working with users to create the programs and services that they participate in or engage with. In working with children or teens, co-design is one way to cultivate student voice and agency.

- Read this guide [PDF] from the National Equity Project about developing youth-adult design partnerships in schools. The resource covers challenges, technical and relational dynamics of co-design work and examples of how co-design can be implemented in all levels of a school. If you’d like, you can read the rest of the resource series here.

- Explore this resource by VRtality which outlines how they structure their co-design sessions with teens. VRtality is a program that uses VR co-design to support teen mental health, but their example session plans can inform other co-design initiatives, including those with younger children.

- Read the article Teen Advisory Boards Work to Impact Libraries and Communities by School Library Journal. The article describes what teen advisory boards are, how they can be mutually beneficial for teens and libraries, and how they can support social justice work.

READ

READ

- Learner Voice Demonstrates Commitment to Building Agency [PDF] – The authors of this blog post discuss how educators can provide a learning environment that encourages learner voice. You’ll definitely want to check out the Continuum of Voice Chart they created.

- Student Choice Leads to Student Voice – In this blog post for Edutopia, learn about how teachers at Science Leadership Academy in Philadelphia cultivate student voice and agency in their classrooms. Be sure to click on the embedded links in the blog post to see examples of student work.

WATCH

WATCH

The video series Is School Enough posted by Edutopia explores how schools can make learning more authentic and relevant to the lives of youth. The examples presented demonstrate the centrality of voice and agency to engaged and active learners.

IMAGES OF PRACTICE

IMAGES OF PRACTICE

Carolina Friends School (CFS) is a Pre-K through grade 12 independent Quaker School located in Durham, North Carolina. Honoring the life and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is an important yearly event for CFS, deeply aligned with their mission — the pursuit of truth, respect for all, peaceful resolution of conflict, simplicity, and the call to service. Each year the CFS community celebrates Dr. King’s birthday and his legacy through song, dance, words, and service. In 2019, Simon Covington, a senior at CFS, wrote and shared this spoken word poem which serves as a call to action for all of us and demonstrates how youth voice can be cultivated in our schools and libraries.

Access a PDF of the poem here to read along while you watch.

Respond

Respond

Reflect on what you’ve learned so far in this module about youth voice and agency. Revisit the list of issues that you think youth in your school, library, or community care about. Now brainstorm a list of ways that library staff can work with youth to cultivate their voices and express their agency. Remember to think collaboratively and focus on youth leadership. Think creatively and boldly.

Stuck? Many public libraries have developed programs to support youth voice and agency. Explore the following examples. As you learn about these programs, consider which aspects you might implement in your community. Think about how you might adapt these programs to a school library context.

Connect

Connect

For voice to be meaningful, there must be those willing to listen.

– Pedro Noguera

As you reflect on Professor Noguera’s quote, think about who (community leaders, non-profit organizations, government agencies, universities, etc.) you might connect with in your community who are willing and ready to listen to the voices and ideas of youth. What resources, strategies, or skills might they help youth develop? What platforms might they provide that allow youth to speak their truths and to share their ideas for change?

Explore

Explore

Learning for Justice’s Framework for an Anti-Bias Curriculum includes social justice standards. In addition to helping students develop knowledge and skills related to prejudice reduction, many of the standards support voice and agency. As you explore the standards, think about how you can work with teachers to incorporate them into the classroom. You will also want to explore the learning plan builder and lesson plans that Learning for Justice has developed to support the development of each standard.

But Wait!

But Wait!

In this section, we address common questions and concerns related to the material presented in each module. You may have these questions yourself, or someone you’re sharing this information with might raise them. We recommend that for each question below, you spend a few minutes thinking about your own response before clicking the arrow to the left of the question to see our response.

Some of the examples you shared seem political in nature. I'm all for cultivating youth voice, but don't think my library will support programs that support youth activism.“If your child can read and learn about police brutality from the safety of a book, that is privilege.” – Angie Thomas

“Youth are already doing activism work whether you know it or not. Rather than try to make something for them, figure out how to support what they’re already doing. Have conversations, create space, offer resources, make connections.” – Gabbie Barnes

“We have reached a critical time in librarianship where the onus may be on us to teach our youth about tolerance, to ask questions, to debate, and to disagree respectfully.” – Megan Burton

References and Image Credits

Bishop, R. S. (1990). “Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.” Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists and others: A plea for narrative. The Michigan Law Review Association, 87, 2411-2441

Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. (1999). Critical Race Theory: The cutting edge, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Johnston, P.H., and Nicholls, J.G. (1995). Voices we want to hear and voices we don’t. Theory Into Practice, 34(2), 94-100.

Mitra, D. L. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106(4), 651-688.

Morrell, E. (2004). Linking literacy and popular culture: Finding connections for lifelong learning. Norwood, MA: Christopher Gordon.

Morrell, E. (2006). Youth-initiated research as a tool for advocacy and change in urban schools. In S. Ginwright, P. Noguera, & J. Cammarota (Eds.), Beyond resistance! Youth activism and community change: New democratic possibilities for practice and policy for America’s youth (pp. 111-128). New York: Routledge.

Oldfather, P. (1995). Songs “come back most to them”: Students’ experiences as researchers. Theory Into Practice, 34(2), 131.

Rudduck, J., & Flutter, J. (2000). Pupil participation and perspective: ‘Carving a new order of experience.’ Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 75-89.

| Go Back: Module 18: "Leveling Up" Your Instruction | You Are Here: Module 19: Student Voice & Agency | Next: Module 20: Talking About Race with Youth |