| Go Back: Module 22: Transforming Library Instruction | You Are Here: Module 23: Transforming Library Space and Policies | Next: Module 24a: Transforming Library Collections Part 1 |

After working through this module, you will be able to:

- Evaluate your library’s physical and digital space and policies through a racial equity lens.

- Collaboratively develop a plan to improve your library’s space and policies to better serve BIYOC.

- Implement your plan and assess the impact of changes to your library’s space and policies on BIYOC.

In most cases, your library’s physical or digital space will be a child or teen’s first introduction to your program. Their first impression of the library can be set in the time it takes to enter its doors. In a plethora of ways, the library space can communicate a sense of welcome, acceptance, excitement, and possibility – or, it can communicate the opposite. The library’s space also explicitly or implicitly communicates information about library policies – what is allowed, encouraged, and prioritized in the space, and what is not. In this module, we will explore research-backed strategies for creating library spaces and policies that are welcoming and affirming for BIYOC, share examples of libraries that are putting these strategies to work, and provide guidelines for effective library spaces and policies that you can use to plan for improvements within your own context.

First, let’s consider effective library spaces.

Read

Read

Most of the guidance that has been published related to library space for children and teens has been written without an explicit focus on race or equity. Still, this guidance can provide us with a useful place to start when we consider the question, “What are the features of an equitable and inclusive library space?”

- Look over YALSA’s National Guidelines for Teen Space. As you read, try to think about each guideline through a racial equity lens. For example, Guideline 1.1 is “Create a space that meets the needs of teens in the community by asking teens to play a role in the planning process.” Considering racial equity in the process of reaching this goal would require librarians to understand the demographics of their service population, consider the assets and strengths of various groups and communities within that population, and ensure that the widest possible variety of teens is invited to participate in the planning process, especially racially marginalized teens.

- Read the article “Learning from Librarians and Teens about YA Library Spaces” by L. Meghann Kuhlmann, Denise Agosto, Jonathan Pacheco Bell, & Anthony Bernier.

- Look over pages 3-11 of Designing Spaces for Effective Learning: A Guide to 21st Century Learning Space Design [PDF]. This report, written by JISC UK, is focused on university learning spaces; however, most of the guidance is also relevant to school and public libraries at all age levels.

- Review Demco’s “Early Literacy Space Planning Guide” [PDF], which focuses on library spaces for children ages four and under.

Review

Review

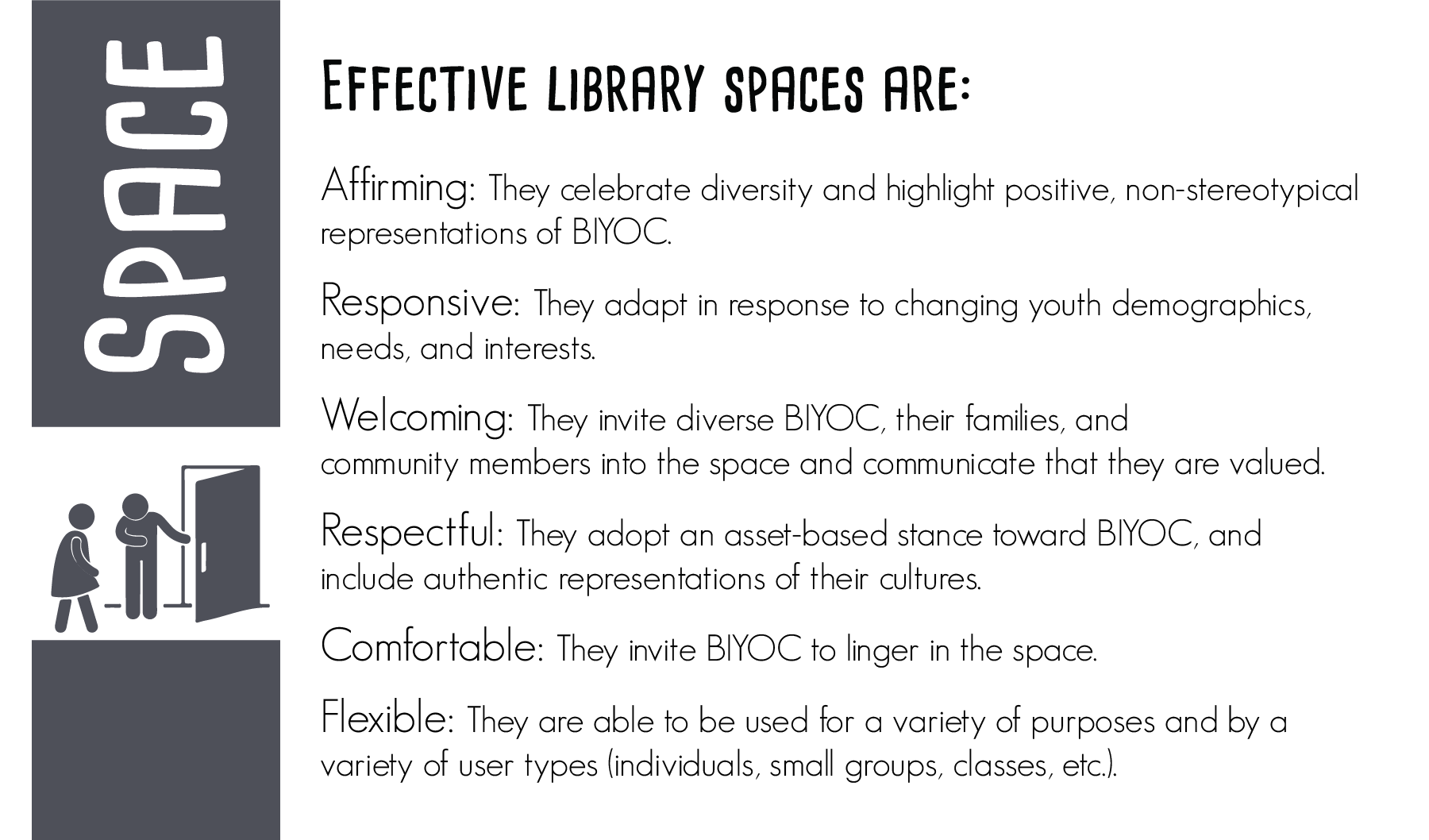

In Module 21, we introduced the five-part framework of Effective Library Services for Diverse Youth. Based on our own research and discussions with diverse youth as well as the research of others working in the library and education fields, we have identified six key features of effective library spaces for BIYOC.

Respond

Respond

In your response journal, reflect on each of the six features of effective library spaces. For each characteristic, come up with 3-5 specific ways that a library might embody that feature: What would a ________ library space look like? Try to think creatively and go beyond your brainstorming ideas from Module 21. Your examples might come from your own library or libraries you’ve visited before, but you can also think outside the box to explore new ways that library spaces might meet these benchmarks. Be sure to consider not only physical space, but also the library’s digital space/website.

When you're done, click here to see some of our ideas - but note that our list is not exhaustive.- Affirming: Posters and bulletin boards feature non-stereotypical images of BIYOC. Books highlighted in library displays feature people of all races and cultures; depictions of BIPOC are featured within all genres (not only in books about Civil Rights or slavery, for example). Diversity within as well as across racial groups is evident in displays and highlighted resources.

- Responsive: High-interest materials are displayed or shelved in a prominent location; these materials rotate with changing youth interests. There is a place for youth to provide feedback and suggestions (for example, a mailbox or online form). Youth are invited to contribute to the space (for example, by sharing their artwork, contributing to message boards, or posting to the website).

- Welcoming: Prominent signage welcomes all children and their families to the library and/or the library website. Signage is displayed in multiple languages. The library entrance is attractively decorated in an age-appropriate way. Security gates are not present. If they are posted at all, library rules are phrased positively (focused on desired behaviors) rather than negatively (a list of “do nots”). If security guards are present, they are not stationed in the teen area, nor do they concentrate their attention disproportionately on the teen area.

- Respectful: The library space communicates to children and teens that they are trusted (for example, by encouraging them to move furniture or allowing them open access to technology). Art, literature, and other elements of diverse cultures are used in an authentic and non-appropriative manner within the space (physical and digital). As an example of what NOT to do, we saw an “author totem pole” in one library that consisted of author images – all but one of which was a white male – topped with a Native American figure. Using a totem pole, which has complex and symbolic meaning for many Indigenous communities, in this way fails to respect Native culture.

- Comfortable: Furniture is age-appropriate and suitable for a range of users. Options such as bean bag chairs, standing desks, and wobble or ball chairs are provided to help all children and teens be productive and comfortable within the space. Institutional features such as fluorescent lighting, colorless walls and furniture, and immovable shelving and furniture are minimized, removed, or hidden if possible.

- Flexible: Furniture and shelving are movable. The library is arranged so that multiple distinct areas are available (for example, a quiet space, a classroom space, and a social space). The library website takes into account major user groups (for example, students, teachers, and parents) and offers a different user experience for each.

Images of Practice

Images of Practice

At the Beatties Ford Regional Public Library in Charlotte, North Carolina, Teen Specialist Jamey Rorie works to ensure that all of the library’s teen users feel ownership of the space. He has worked with his colleagues to design spaces, programs, and services that welcome BIYOC into the library and invite them to play a major role in shaping the space. In the video below, you’ll see not just the Beatties Ford space, but also how teens interact with it. As you’re watching, think about what characteristics of effective library spaces for diverse youth are evident here.

School librarian Kathryn Cole was able to cross a major item off her professional bucket list when she was given the opportunity to build a new library program from the ground up – literally. Kathryn was hired at Northside Elementary School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, as part of the team that designed and launched the new school. In the years since the school was built, Kathryn has continued to improve her library’s physical space, always with a focus on students. Watch the video below and view the image slideshow to see images of the NES Library. As you’re watching, think about what characteristics of effective library spaces for diverse youth are evident at Northside.

Getting the chance to design your own library space from scratch is rare. In most cases, you will need to make the most of the space you’re given. That was the case for Julie Stivers, former school librarian at Mount Vernon Middle School in Raleigh, North Carolina. Mount Vernon is an alternative school for students who have not experienced academic success at their base (neighborhood) schools. The library space at Mount Vernon is very small (roughly 25′ x 25′), and when Julie first arrived, the space was not inviting or attractive. Over the course of several years, Julie has transformed this space in ways that meet the needs of Mount Vernon’s students, the majority of whom are Latinx or Black. View the image slideshow to see images of the Mount Vernon Library and read the captions for more information about the library space. Think about which characteristics of effective library spaces for diverse youth are evident at Mount Vernon.

The physical library space is vital to an effective library program, but library spaces can also be digital. Before a child or teen visits your library in person, they may visit your library’s website. The same characteristics of effective physical spaces also apply to digital spaces. In the slideshow below, we have compiled screenshots of school and public library websites designed for children, teens, and/or their families. For each of these images, we have noted at least one way that the site illustrates one or more of the characteristics of effective library spaces.

Act

Act

Like improving other aspects of your library services, improving your library’s physical and digital space should begin with an assessment of your current environment. If you haven’t already done so, use the Culturally Sustaining Library Walk tool (introduced in Module 21) to collaboratively assess your current library’s space. Don’t forget about your digital space, and be sure to include input from BIYOC.

After assessing your current space, set three goals for improving your library space: one short-term goal that you can accomplish immediately, one medium-term goal that you can accomplish over the next several weeks, and one long-term goal that you can accomplish over the next year. Use the Goals for Improving Library Services for Diverse Youth [PDF] template to write these goals down. We suggest printing this document (in poster size if possible), laminating it, and using it to track all of your goals related to the material in the next several modules. Post these goals somewhere in your library, and work with youth and other library stakeholders to achieve them. Once you have achieved a goal, replace it with another one.

Library Policies

Your library’s physical and digital space provides visitors with explicit and implicit information about how your library and its resources can be used, and by whom. Your library’s policies, both written and applied, also shape visitors’ understanding of who and what is welcomed in the space.

Your library policies may take multiple forms. Some policies are formal, written, and shared publicly with the library community. Often, this type of policy takes the form of a set of rules that must be followed in the library. Formal policies can also include collection development criteria, official procedures for book challenges, and guidelines for use of the library’s space and resources. In some cases, you might not have much control over this type of policy – for example, in some school districts, a board policy document supersedes any local decisions. Or, you may have the ability to revise or completely rewrite your library’s formal policy documents. Either way, you do have control over another type of library policy: informal, de facto policies that are enacted and enforced within the day-to-day interactions between librarians and library users. This type of policy is unwritten but no less important to structuring the library environment.

As an example of how these two types of policies interact, let’s examine one of the official policies of an actual public library system. This library system serves a diverse urban and suburban population and has seven branch library locations in addition to the main downtown branch. The system has a centralized policy document that applies to all branches. Officially, the policy for all eight libraries within this system is that:

Children age 10 and under are to be supervised and must remain in the physical presence of the parent, guardian or caregiver age 18 or over during the child’s entire visit to the library.

Think about this policy from an equity lens. Though the policy is race-neutral on its face, we know that youth of color are more likely to live in single-parent homes. We also know that wealth disparities (discussed in Module 1b) mean that families of color are disproportionately unable to pay for afterschool and summer childcare compared to white families. Often, older siblings (teens and tweens) are responsible for supervising their younger siblings while their parents are at work. Under this policy, however, a child under 10 would not be permitted in the library space if accompanied only by a teenage sibling.

Of course, libraries need policies that will maintain safety for all of their users, and having an unaccompanied six-year-old in the library poses unacceptable risks for the child. However, limiting supervision to only adults has a disproportionate impact on families of color, and forces these families to find other public accommodations that may be less safe than the library. In addition, this policy takes a deficit view of youth, in that it implies that teenagers are unable to effectively supervise a younger charge. Technically, this policy also prohibits many teenage parents from bringing their children into the library.

Although this is the official library system policy, there are many ways that individual libraries and librarians might enact this policy in a way that takes varying family needs and compositions into account. For example, libraries might offer an intergenerational program after school hours, where (unrelated) children and senior citizens participate in activities together. They may work with local organizations to arrange tutors and mentors to work with children during afterschool hours and during the summer. Of course, librarians may also choose to simply “look the other way” and fail to enforce this policy in their space. A better option, however, may be to advocate on behalf of or with teens at the system level to change this policy.

For a deeper discussion of library behavior policies and how they may disproportionately impact BIYOC, see Module 15, specifically the “Discipline and Related Policies in the Library” section.

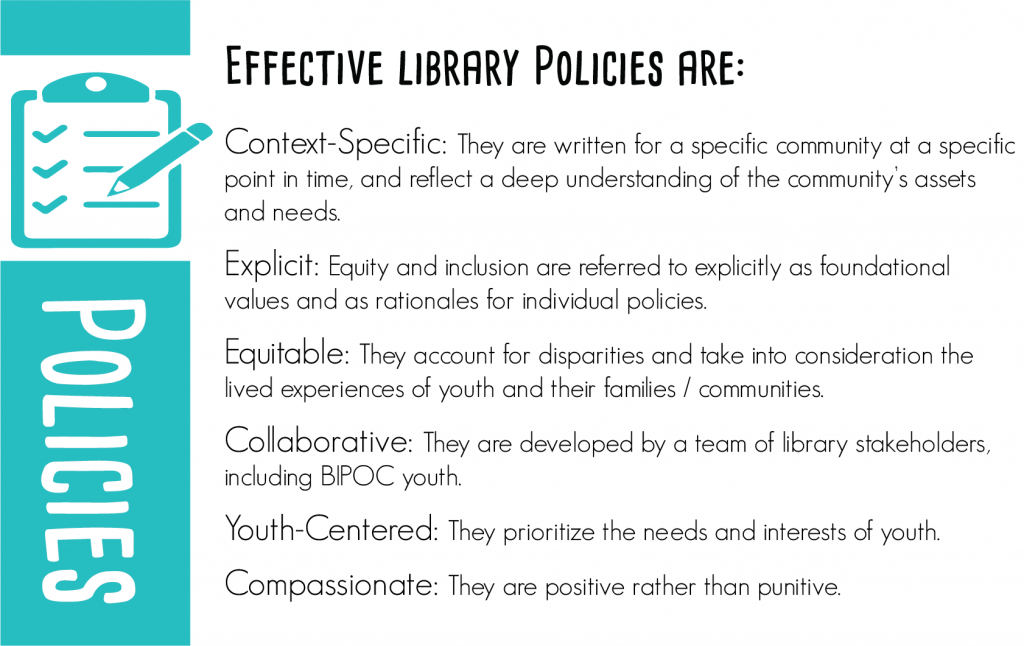

In Module 21, we introduced the five-part framework of Effective Library Services for Diverse Youth. Based on our own research and discussions with diverse youth as well as the research of others working in the library and education fields, we have identified six key features of effective library policies for BIYOC:

Respond

Respond

In your response journal, reflect on each of the six features of effective library policies. For each characteristic, come up with 3-5 specific ways that a library might embody that feature: What would ________ library policies look like? Try to think creatively – your examples might come from your own library or libraries you’ve visited before, but you can also think outside the box to explore new ways that library policies might meet these benchmarks.

When you're done, click here to see some of our ideas - but note that our list is not exhaustive.

- Context-Specific: Written policies describe the community for which they are written and take into account its unique strengths and needs. Informal/enacted policies are based on a deep understanding of the community served by the library. Policies are regularly updated to reflect changing community needs, interests, and makeup.

- Explicit: Collection development policies include diversity (of characters and authors) as a primary criterion for selection. Equity is discussed in written policies as a foundational library value. Librarians focus conversations about enacted policies or proposed policy changes on equity.

- Equitable: As new policies are developed and when reviewing existing policies, stakeholders consider their impact on BIYOC and their families. BIPOC children and teens and their family members are consulted about existing and proposed library policies. The library does not charge fines for late materials. Library hours are determined with the needs of marginalized community members in mind.

- Collaborative: BIPOC children and teens are involved in the process of writing and revising library policies. Procedures are in place for youth to challenge and/or discuss existing policies with librarians and librarians welcome and encourage these conversations.

- Youth-Centered: Policies take into account the activities, resources, and services that youth want in their library space.

- Compassionate: Library codes of conduct are developed with youth and are phrased in terms of desired behavior rather than prohibited behavior. If and when undesirable behavior occurs, librarians address it positively (for example, by speaking with the children and teens involved or by using restorative justice techniques) rather than punitively. Librarians understand that policies are guidelines, but may not be appropriate to apply in every situation with every child or teen, and they are willing to “bend the rules” when it is in the best interest of the children and teens they serve.

Act

Act

If you haven’t already done so, use the Culturally Sustaining Library Walk tool (introduced in Module 21) to collaboratively assess your library’s current policies. As you work through this process, examine both your written and unwritten library policies. You may find it helpful to take photos of places in your library where rules or expectations are posted explicitly or suggested implicitly by the setup of the space. Be sure to include input from BIPOC children and teens; they may notice many implied policies that are “invisible” to you as the librarian.

After assessing your current policies, set three goals for improving them: one short-term goal that you can accomplish immediately, one medium-term goal that you can accomplish over the next several weeks, and one long-term goal that you can accomplish over the next year. Use the Goals for Improving Library Services for Diverse Youth [PDF] template to write these goals down. We suggest printing this document (in poster size if possible), laminating it, and using it to track all of your goals related to the material in the next several modules. Post these goals somewhere in your library, and work with youth and other library stakeholders to achieve them. Once you have achieved a goal, replace it with another one.

But Wait!

But Wait!

In this section, we address common questions and concerns related to the material presented in each module. You may have these questions yourself, or someone you’re sharing this information with might raise them. We recommend that for each question below, you spend a few minutes thinking about your own response before clicking the arrow to the left of the question to see our response.

I would love to use these ideas, but I don't have any funds available to redesign my library space.My library's policies are set by the school district/county. What can I do if I don't have any official control over the policy documents?

Many library policies are not developmentally appropriate and this can be challenging for library staff. In public libraries, everyone is expected to serve youth so how you can help library staff understand the developmental needs of youth? In some communities, there may be pediatricians, child psychologists, or educators who would be willing to provide workshops for library staff on youth development. National organizations like the Association of Middle Level Education or the National Association for the Education of Young Children often also provide workshops (face-to-face and online) for a fee. Many free online resources also exist that can be used to educate library staff about children and adolescent development. We’ve listed a few here:

| Go Back: Module 22: Transforming Library Instruction | You Are Here: Module 23: Transforming Library Space and Policies | Next: Module 24a: Transforming Library Collections Part 1 |