| Go Back: Module 5: Systems of Inequality | You Are Here: Module 6: Indigeneity and Colonialism | Next: Module 7: Exploring Culture |

This module was written by Naomi Bishop. Naomi is a Research Librarian at Northern Arizona University and earned her MLIS at the University of Washington. She is a past President of the American Indian Library Association and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community (Akimel-O’odham/Pima).

This module was written by Naomi Bishop. Naomi is a Research Librarian at Northern Arizona University and earned her MLIS at the University of Washington. She is a past President of the American Indian Library Association and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Community (Akimel-O’odham/Pima).

AFTER WORKING THROUGH THIS MODULE, YOU WILL BE ABLE TO:

- Define colonialism.

- Describe the lasting impacts of colonialism on Native people.

- Describe issues related to Native identity that affect today’s children and youth.

Introduction

The history of the United States taught in U.S. schools often times does not teach students about the Indigenous People of the United States and the genocide and colonization on the land we live on today. This module provides context and consideration for Native Americans living in the U.S. today. Students in the United States must understand that before Columbus, the tribal nations and lands of America belonged to Indigenous people from numerous distinct tribes, languages, and cultures.

Today the United States government recognizes 562 tribal nations as having rights of sovereign self-government. There are also dozens of other tribes recognized by various state governments, whose authorities and responsibilities differ according to the laws of the states. Within the U.S. there are 310 federally recognized reservations (Dunbar-Ortiz, 2014). Treaties are the supreme law of the land; negotiated with the federal government, they make tribal sovereignty a legal status that the court must address. A variety of historical policy periods have had a major impact on American Indian people’s abilities to self-govern.

Read

Read

Understanding the political culture of tribal nations is critical to understanding other elements of Native culture. Read “Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction,” developed by the National Congress of American Indians (note: this is a large PDF and may take a while to load). This guide provides a basic overview of the history and underlying principles of tribal governance.

Key Terms and Definitions

Indigenous- Originating or occurring naturally in a particular place

Native American – All Native peoples of the United States and its trust territories (i.e., American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Chamorros, and American Samoans), as well as persons from Canadian First Nations and Indigenous communities in Mexico and Central and South America who are U.S. residents.

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN)- Persons belonging to the Indigenous tribes of the continental United States (American Indians) and the Indigenous tribes and villages of Alaska (Alaska Natives).

Colonialism– The policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.

Treaty-a written agreement between two or more countries, formally approved and signed by their leaders

Sovereignty– The authority of a state to govern itself.

Tribal sovereignty – tribes govern themselves in order to keep and support their ways of life, cultural, political, and economic bases.

Reservation- An area of land set aside for North American Indians.

Explore

Explore

Read over the information shared in the slides below, which summarize the issues that Native people, especially Native children and teens, are dealing with today, and the historical and political background of those issues.

Watch

Watch

If you were told that you had to leave your home and go live somewhere else far away, how would you react? The video below, produced by the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, captures the responses of middle school students who learned about the history of American Indian removal.

In the video below, produced by Teen Vogue, seven Native American young women debunk common misconceptions about their culture. As you watch this video, think about which of these misconceptions you may have heard or believed in the past.

What questions do non-Native children have about indigenous people? Some of those questions are shared and answered in this video from HiHo Kids, in which children meet Native American politician Asa Washines, a Tribal Council Member for the Yakima Nation Tribe in Washington State.

Explore

Explore

What are the names of Tribes in your geographic region? Which Tribes used to occupy the land on which you now live? Answering this question fully may take some independent research, but the Native Land mapping site can help you get started. The creator of the site, Victor Temprano, is not himself Native, however many of the contributions to the site have come from Native people. Temprano decided to create the site after doing some independent research related to pipeline projects in 2015 and writes on the site’s About page that:

I feel that Western maps of Indigenous nations are very often inherently colonial, in that they delegate power according to imposed borders that don’t really exist in many nations throughout history. They were rarely created in good faith, and are often used in wrong ways.

The Native Land site also contains a Teacher’s Guide that provides educators wishing to use the maps with a set of essential questions, a historical primer, and links to additional resources.

Read

Read

Dr. Debbie Reese is a nationally recognized scholar on issues of Native representation, specifically Native representation in books for children and teens. She is tribally enrolled at Nambe Owingeh, a federally recognized tribe, and maintains the American Indians in Children’s Literature blog (an excellent source for a wide range of resources related to her areas of expertise). Read her 2018 article, linked below, to help connect the foundational material in this module to issues of practice for school and public librarians.

Reese, Debbie. Critical Indigenous Literacies: Selecting and Using Children’s Books about Indigenous Peoples [PDF]. Language Arts. Volume 95, Number 6, 389-393. July 2018

Who is…

Dr. Debbie Reese

Dr. Debbie Reese is tribally enrolled at Nambe Owingeh Pueblo, a federally recognized tribe. Her long history of work on the representation of Native people in children’s literature was recognized in 2019 when she received the May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture Award from ALA.

To learn more about Dr. Reese and her work:

Connect

Connect

After reading Dr. Reese’s article, check for understanding by completing the following quiz. Click on the question to show the answer.

What year did the then President declare November as National Native American Heritage Month?

What did European and then U.S. leaders enter into with leaders of Native nations who inhabited the lands from the beginning?

What does critical Indigenous literacy encourage children to do?

What critical questions should you ask about misrepresentations of American Indians?

What actions can teachers and librarians take to bring Native voices and stories into the classroom?

Reflect

Reflect

Based on what you have learned in this module, record your answers to the following questions in your journal. In later modules, we will return to some of these questions as we explore ways to practice Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy with Native children and teens.

- What are some of the lasting impacts of colonialism on Native People?

- What are some issues related to Native identity that affect children and youth today?

- What do Native Americans today want you and your students to know about them?

But Wait!

But Wait!

In this section, we address common questions and concerns related to the material presented in each module. You may have these questions yourself, or someone you’re sharing this information with might raise them. We recommend that for each question below, you spend a few minutes thinking about your own response before clicking the arrow to the left of the question to see our response.

Who are experts on issues of Native authenticity and tribal sovereignty?Each tribal community has its own distinct membership and government. Tribal Nations determine their own laws, protocols, and citizenship. Members of tribal Nations may self-identify or have an enrolled status to a specific community. “The governmental status of tribal nations is at the heart of nearly every issue that touches Indian Country. Self-government is essential if tribal communities are to continue to protect their unique cultures and identities. Tribes have the inherent power to govern all matters involving their members, as well as a range of issues in Indian Country.” http://www.ncai.org/about-tribes

What do I do with problematic materials already in my collection?

Librarians should have a collections and reconsideration policy that addresses acquisition and deaccession; advice for such a policy is available at http://www.ala.org/tools/challengesupport/selectionpolicytoolkit. The question of whether to leave problematic materials on the shelf is a complicated one, bringing up issues of censorship and intellectual freedom. In an AICL blog post, Dr. Debbie Reese suggests carefully examining the “ramifications of using books with such language… and NOT engaging students in critical discussion of such words and phrases.” She further suggests that instead of assigning these books in English classrooms, they may be better suited for history / social studies courses, where they can be placed in the proper historical context and critically examined.

We would like to point out that a growing number of Indigenous authors and illustrators are producing excellent work, often through small independent publishers, and we would encourage librarians to take advantage of this opportunity to seek out other Native American works to enjoy and purchase for your collections.

I have to order my library books from specific vendors, and I can't seem to find high-quality books by Native authors / about Native issues from those sources. What do I do?

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

- Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian Native Knowledge 360: http://www.nmai.si.edu/nk360/

- American Indian Library Association: https://ailanet.org/

- American Indians in Children’s Literature https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/

- National Museum of the American Indian Nation to Nation Online Exhibit: http://nmai.si.edu/nationtonation/

- National Museum of the American Indian Americans Online Exhibit: https://nmai.si.edu/americans/

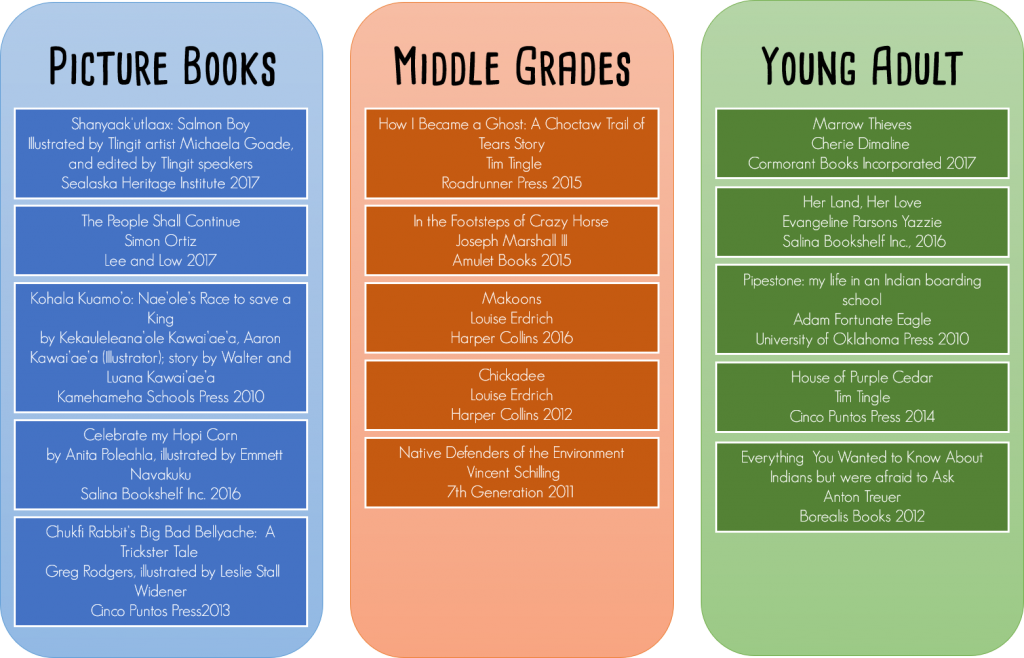

Some Children’s and Youth Books that Share Stories by Native Voices (list created by Naomi Bishop, MLIS):

References

Bigelow, B. and Peterson, B. (1998). Rethinking Columbus: The next 500 years 2nd Edition. Rethinking Schools.

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014). An Indigenous Peoples’ history of the United States. Boston: Random House.

National Congress of American Indians. Tribal nations and the United States: An introduction. Retrieved from http://www.ncai.org/about-tribes.

Treuer, A. (2012). Everything you wanted to know about Indians but were afraid to ask. Saint Paul, MN: Borealis Books.

Reese, D. (2018). Critical Indigenous literacies: Selecting and using children’s books about Indigenous Peoples. Language Arts, 95(6), 389-393.

“We are still here”: An interview with Debbie Reese. (2016). English Journal, 106(1), 51.

The National Museum of the American Indian Education Office. Native Knowledge 360 Framework for Essential Understandings about American Indians. Retrieved from http://www.nmai.si.edu/nk360/pdf/NMAI-Essential-Understandings.pdf.

| Go Back: Module 5: Systems of Inequality | You Are Here: Module 6: Indigeneity and Colonialism | Next: Module 7: Exploring Culture |