| Go Back: Module 1b: Introduction | You Are Here: Module 2: History of Race and Racism | Next: Module 3: Defining Race and Racism |

After working through this module, you will be able to:

- Describe how and why the concept of race was developed.

- Explain how the concept of race was applied throughout history in ways that advantaged white people and disadvantaged people of color and Native people.

- Outline how historical advantages and disadvantages based on race have accumulated to create and maintain the racial inequities we observe today.

- Connect historical events and trends to your own personal and family history.

Introduction

In Module 1, we examined some of the statistics related to racial inequity in the United States today. The large, and in some cases growing, life outcomes gaps between Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) and white people did not develop overnight but are instead the product of centuries of accumulated inequity. In this module, we will walk through the history of race and racism in the United States. Before we begin, there are two important things to note:

- The history presented below is partial, as are all narratives of history. We focus on the evolution of the concept of race and the development of systemic racism in the United States, and present major events and turning points in those narratives. By necessity, there will be events, people, and perspectives that are left out. Additional resources are linked throughout the module that can help you delve more deeply into the issues presented here.

- The history presented below tells a different story about the United States than what is typically presented in K-12 classrooms, and this different story may be challenging or surprising to you. Many scholars have written about the “master narratives” communicated in K-12 history textbooks used in U.S. public schools. Typically, those narratives go something like this: The United States is a land of promise, founded on the idea that all men were created equal. Though America has faced many challenges during its history, we have always overcome them. In the United States, progress is inevitable, both for the nation itself and for individual citizens, who can all achieve the American Dream if they are willing to put in the work. This presents history as a one-way street; an inspiring story featuring a cast of heroes and the assurance of a happy ending for all. The reality of U.S. history is much more complex; for many, the United States has been a land of broken promises and oppression. The narrative below will serve as one counterpoint to the “land of promise” theme. For additional counternarratives, the five books featured in the sidebar (right) are an excellent starting point.

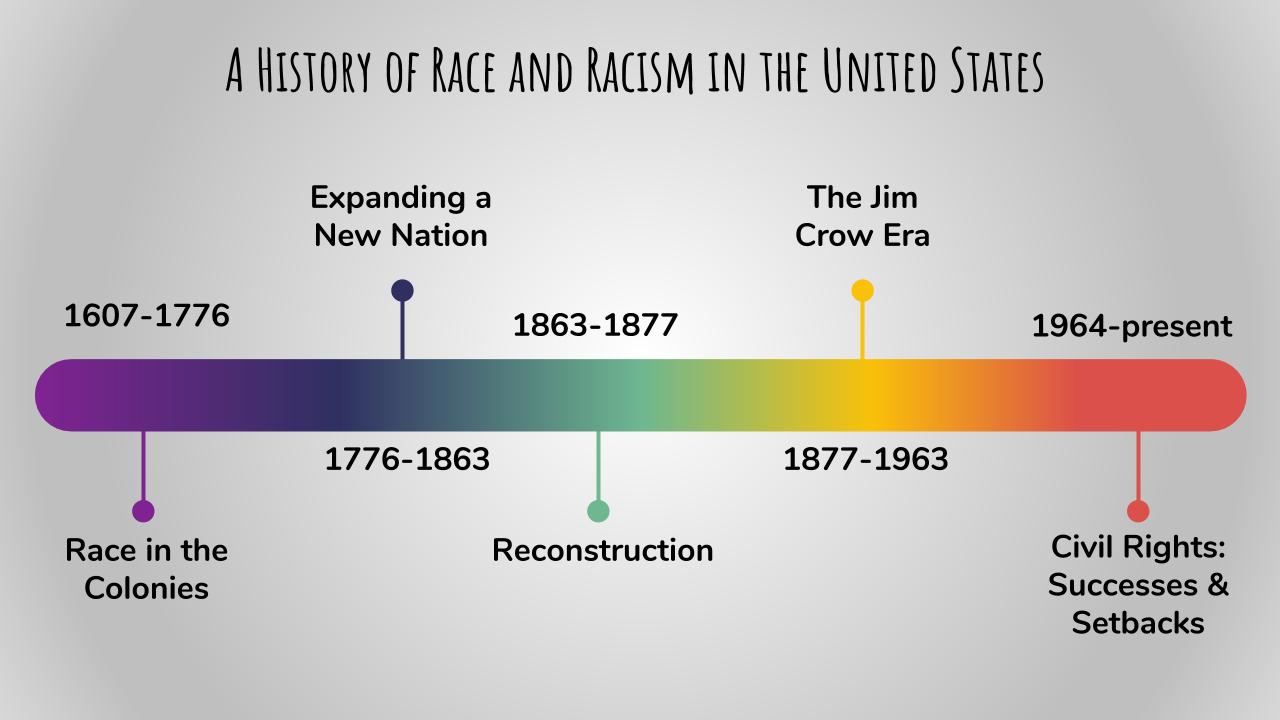

This module will be presented in five chronological parts, shown in the image below. As you work through this module, we would like you to keep the following “big picture” questions in mind (these are included in your journal so that you can take notes as you work through the module):

If you identify as Black, Native American, or as a person of color: what comes up for you in terms of your own experiences with racism? Learning history at school? What are you curious about?

If you are a person who identifies as white: based upon your experiences related to race, racism, culture, and history in the U.S., what have you been introduced to in this module that is new, surprising – maybe even upsetting or disorienting? What are you curious about?

Historical Counternarratives

In addition to the material presented in this module, the five books below offer excellent starting points to begin broadening your perspective on United States history:

A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn

A People’s History of the United States by Howard Zinn

This influential book, first published in 1981, tells America’s story from the point of view of women, factory workers, African-Americans, Native Americans, and immigrant laborers, challenging the “Great Man” narrative of history.

Lies my Teacher Told Me by James Loewen

Lies my Teacher Told Me by James Loewen

The 2018 edition of this seminal book includes new material related to the Trump presidency. Beginning with pre-Columbian history, Loewen critiques the ways that history is taught to students in U.S. schools and offers a compelling alternative.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz

In this 2015 book, Dunbar-Ortiz offers the first history of the United States told entirely from the perspective of Indigenous people, focused on Native resistance to centuries of U.S. expansion.

An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Paul Ortiz

An African American and Latinx History of the United States by Paul Ortiz

This 2018 text challenges the notion of westward progress by placing African American and Latinx voices at the center of American history. Ortiz narrates a long and continuing story of the working class organizing against imperialism.

The Making of Asian America by Erika Lee

The Making of Asian America by Erika Lee

This 2016 book traces the long and complicated history of Asian immigrants and their American descendants from the 1500s to the present. Lee explores how perceptions of Asian Americans have changed over time, and how their history has interacted with and shaped the history of our nation itself.

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America by Ibram X. Kendi

This National Book Award winning text traces the historical development of racist ideas in the United States. A 2020 “remix” by Kendi and Jason Reynolds adapts the content for a young adult audience.

Module Overview:

Part One: Race in the Colonies

The concept of “race” as we know it today is relatively new. When what is now the United States was first colonized by British settlers, the ideas of “white” and “black” did not yet exist as racial categories. Over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, relations among European colonists, Native Americans, and Africans changed in ways that would establish a racial hierarchy that in many ways persists to this day.

The materials below will provide an overview of race and racism in the colonial period.

Before you begin, take a moment to record in your journal what you already know about race and race relations in the American colonies.

While you review the slideshow, think about these questions:

- What qualities gave someone status and power in the earliest days of American colonialism, and how did that change over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries?

- In what ways were racial categories used to divide and oppress early Americans and concentrate power among elite whites?

- How does the history presented here expand, reaffirm, or complicate your previous understanding of race and racism in Colonial America?

Note: we recommend viewing this and the other slideshows in this module in full-screen mode (use the controls at the bottom of the slide window to switch to this view).

Reflect

Reflect

Writing about early American settlers, sociologist Kai Erikson said: “One of the surest ways to confirm an identity, for communities as well as for individuals, is to find some way of measuring what one is not.” In your journal, reflect on this quote as it relates to race in the colonies: in what ways did European colonists define themselves and others by “what one is not?” What were the short- and long-term consequences of this?

Explore

Explore

Visit a museum that contains artifacts related to this period of history. Examine whether and how race is treated in these spaces. For an example of how you might approach this exercise, see Tom Smith’s blog post “Are All Men Created Equal?” in which he explores the treatment of race in three different museums – the American Revolution Museum in Yorktown, Virginia, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture. If you can’t visit a museum in person, explore the educational materials provided through one or more museum’s websites. Museum websites that include material relevant to the Colonial period include:

- the Historic Jamestown site

- Colonial Williamsburg’s Learn page

- the Frontier Culture Museum site

- the Charleston Museum site

- “The People of the Plantation” site from Monticello

- the Learn page of Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest site

Part Two: Expanding a New Nation

After the American Revolution, the newly-formed United States focused on developing the ideological and legal frameworks that would govern the nation, and on expanding that nation beyond the original 13 colonies. This involved grappling with the question of who, precisely, was included in “We the People of the United States,” and who would be excluded from that group and from the rights and privileges it conferred. This period of American history is often referred to as “Westward Expansion”; however, that phrase centers the experiences of white settlers, rather than, for example, the Indigenous people who already occupied the land into which those settlers were expanding. In this segment, we will try to unpack the impact of expansion on Indigenous people, enslaved African Americans, and others who were excluded from citizenship rights in the post-Revolution period.

Before you begin, take a moment to record in your journal what you already know about the period between the American Revolution and the beginning of the U.S. Civil War, specifically what you know about the legal, economic, and social status of African and Native Americans during this time.

While you review the slideshow, think about these questions:

- What are the benefits and responsibilities of citizenship in a country? How were these benefits and responsibilities distributed in post-Revolutionary America, and what are the lasting consequences of this distribution?

- How does the history presented here expand, reaffirm, or complicate your previous understanding of race and racism in post-Revolutionary America?

Note: we recommend viewing this and the other slideshows in this module in full-screen mode (use the controls at the bottom of the slide window to switch to this view).

Reflect

Reflect

In the documentary series Race: The Power of an Illusion, California Newsreel and PBS make the case that the United States has a “long history of affirmative action – for whites.” At this point in the module, what thoughts and/or feelings arise for you in response to this idea?

Part Three: Reconstruction

In the influential book Lies My Teacher Told Me by James Loewen (linked above, sidebar), Loewen summarizes what he calls the Confederate myth of Reconstruction:

Reconstruction was a time when African Americans took over the governing of the Southern states, including Mississippi. But they were too soon out of slavery, so they messed up and reigned corruptly, and whites had to take back control of the state governments. (Loewen, 2007, pp. 156-157)

If you grew up in a former Confederate state, this narrative about Reconstruction might be familiar to you from your own K-12 education. In fact, however, every part of this myth is wrong. Reconstruction was an immensely complex time, set apart from the rest of U.S. history by the rapid expansion of rights for Black Americans. For a short time, it seemed that racial equality – at least between Black and white Americans – might truly be attainable. As we know, that goal was derailed. The materials in this section will explore the progress made by Black Americans during Reconstruction, and the factors that led to the end of that progress.

Before you begin, take a moment to record in your journal what you already know about the Reconstruction period.

While you review the slideshow, think about these questions:

- What were the political, economic, and social impacts of Reconstruction on different populations in the South, and in what ways are those impacts still being felt today?

- How did Black communities take advantage of Reconstruction policies to gain individual and collective power, and what was the response to this among whites in the North and South?

- How does the history presented here expand, reaffirm, or complicate your previous understanding of race and racism in the Reconstruction period?

Note: we recommend viewing this and the other slideshows in this module in full-screen mode (use the controls at the bottom of the slide window to switch to this view).

Reflect

Reflect

Now that you have worked through the slideshow, return to what you wrote down as your prior knowledge about Reconstruction. How did the information presented here reinforce, complement, or challenge your previous understandings?

Part Four: The Jim Crow Era

As support for Reconstruction governments waned and the South experienced ongoing economic depression, the nation entered a new era that is commonly regarded as the low point of race relations in the United States: the Jim Crow era. The materials below will explore the factors that led to this decline in race relations, and the ongoing impact of this period on race relations today.

Before you begin, take a moment to record in your journal what you already know about race and race relations in the Jim Crow era.

While you review the slideshow, think about these questions:

- In what ways were Jim Crow laws a response to social and economic realities in this time period, and in what ways did these laws help create those realities?

- Each of the topics discussed in this slideshow (the prison labor system, Jim Crow laws, racial violence, and discriminatory impacts of the New Deal) had impacts that continue to be felt today. What connections can you draw between these events and modern issues?

Reflect

Reflect

At this point in our exploration of U.S. racial history, we have reached the point where you or some of your close relatives may have been alive. Think about the information presented in this section, and write in your journal about any personal or familial connections you may have to these topics.

After you have written your response, click here to see how one Project READY team member responded to this prompt.

I grew up in a military family – my father served in the Army, my brother served in the Marines, and both of my grandfathers served in the 1940s and 1950s. My paternal grandfather took advantage of the GI Bill to get a job at Exxon and purchase a home for himself, my grandmother, and their three children. He stayed at Exxon for the rest of his career, and fully paid off the mortgage on their home. My grandfather passed away several years ago, and my grandmother now suffers from dementia. When it became clear that my grandmother needed to be in a full-time care facility, my dad discovered that as part of his Exxon benefits, my grandfather had been able to sign up for long-term care insurance for himself and for my grandmother. That policy, which my grandparents paid $31 per month for, now pays the full balance of my grandmother’s assisted living care each month – currently over $5,000 and expected to rise as her need for assistance increases. Her home was sold and the proceeds are now in a bank, and will eventually be inherited by my father and his two siblings. My father also used GI Bill benefits to obtain his master’s degree and to secure a low-interest loan on our family home. Because his parents were financially secure (also thanks to the GI Bill), my father has been able to save a good deal of money that may otherwise have been spent on their care. Some of that money went to put my brother and me through college, so I too have benefited from the GI Bill in that way.

My family members are all white. I imagine what might have been if my grandparents and parents had worked just as hard, but were Black. My grandfather would almost certainly not have been hired at Exxon, but instead at a low-paying job that would not allow him to save nor offer him long-term care insurance as a benefit. He may not have been able to purchase a home at all, and if he could, it would probably have been in an area where the home would not appreciate in value. My father could have still taken advantage of the GI Bill benefits, which by his time were much less racially discriminatory in their impact, but because his parents would not have benefited in the same way, much of my father’s income would have had to go toward supporting his parents. He could not have saved the way he was able to as a white person, and as a result, I may not have been able to attend college (at least, not the college I went to). I am proud of everything my parents and grandparents have accomplished, but I have to acknowledge that their race – our race – has played a big role.

Part Five: Civil Rights Successes and Setbacks

What’s past is prologue.

-William Shakespeare

We are not makers of history, we are made by history.

-Martin Luther King, Jr.

Both of the quotes above, written at vastly different times in our world’s history, speak to the idea that our present reality is inextricably linked to our past. The material presented in this module is intended to illustrate that fact on both the personal and the societal level. Because race has historically determined outcomes in our country, race continues to determine outcomes today. Race is not the only factor that determines life outcomes, of course; one’s gender, sexual orientation, disability status, religion, other cultural and physical characteristics, and yes, work ethic also contribute to shaping the choices and opportunities a person has access to throughout their lives. Each of these factors is also shaped by history; as we have done here for race, you could explore the history of gender in the United States, or the history of disability, for example.

Read

Read

A team of graduate-level educators in North Carolina developed a powerful activity designed to open their students’ eyes to the continuing impact that historical racism has on today’s world. These instructors invited their students to play the board game Monopoly, but with one important twist: each student was placed into a group, and each group started the game at a different time. Students in Group 1 began the game and played for 30 minutes before students in Group 2 were allowed to join. Another 30 minutes later, students in Group 3 were permitted to join. The rules of the game were the same for each player: upon entering the game, all players were given $1500, and all players started on the same board location. Each time players passed “Go,” they were given $250. Yet because of the staggered entry times, students found that the winner of the game virtually always came from Group 1. Furthermore, players in Groups 2 and 3 often lost the desire to play the game at all, with some preferring to stay in jail where at least they would not have to pay rent to the Group 1 players who had bought up all the available property before they even joined the game.

Hopefully, the connections between this activity and the history we have just examined are clear. Black Americans, along with other BIPOC, were kept “out of the game” of property ownership and citizenship rights for the majority of this country’s history. Like the Group 2 and 3 players in the Monopoly analogy, by the time BIPOC were legally permitted to own homes and exercise citizenship rights, the majority of the property and power were already concentrated in the hands of white people, making it difficult for BIPOC to build either financial or social capital even when the laws (the rules of “the game”) treat them equally.

Professor David Shih, a Chinese American who blogs about race and racism in the United States, argues that while the Monopoly game is an instructive analogy for understanding today’s wealth disparities, to make the experience even more accurate, additional changes would be necessary:

- All men in Group 3 (representing Black men) should have to go directly to jail if they roll a 4, 5, or 6 on their first throw of the dice (analogous to the fact that 1 in 3 Black men in America can expect to go to prison in their lifetimes). All railroad and utility spaces (e.g. interactions with governmental authority) count as “Go Directly to Jail” spaces for players in Group 3.

- Rolling “snake eyes” (two 1’s) while in jail results in the immediate end to the game for players in Group 3; this represents dying while incarcerated.

- If you are in Groups 2 or 3, your dice rolls while in jail determine the extent to which your salary in the game is reduced for future trips around the board.

- If you are in Group 1 and a Group 2 or 3 player manages to buy property your neighborhood, the rent values of the properties in that set will be cut in half after two turns.

- If players in Group 1 then decide to sell their property in an integrated neighborhood, they can purchase another property in a “better” neighborhood immediately without having to land on the space first.

Dr. Shih outlines more of these rule alterations on his blog post, “What Monopoly can teach us about Ferguson.”

Explore

Explore

Most of the history presented in this module has been collective. To complement this, it is also important to explore personal narratives that show firsthand accounts of how the United States’ racial history impacted individuals and their families. Explore the resources below to find at least one personal narrative that interests you. Or, search online for other personal historical narratives. If you’re looking for resources related to a specific racial or ethnic group, try a search phrase like “Korean American history primary sources.” Once you’ve found and explored at least one resource, use the Padlet to share a link to the narrative you chose and your reflections or reactions to it.

Personal Narrative Sources:

- Born in Slavery: Library of Congress online collection that contains more than 2,300 first-person accounts of U.S. slavery

- Black Civil Rights: Primary Source Collections Online: Annotated list of online primary source collections related to the 1950s and 1960s civil rights movements, curated by Sam Houston State University Libraries.

- Southern Oral History Program: Online collection of more than 5,000 oral histories curated by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Center for the Study of the American South. Collections of particular interest include African American Life and Culture (Series Q), The Long Civil Rights Movement: The South Since the 1960s (Series U), and Black High School Principals (Series M).

- Digital History’s “Voices” Collections: Online collection of primary source documents related to U.S. history. Collections are organized by both time period and group. Collections of particular interest include Native American Voices, Asian American Voices, and Immigrant Voices.

- North American Immigrant Letters, Diaries, and Oral Histories: Online collection of personal narratives from over 2,000 authors who immigrated to the United States and Canada between 1800 and 1950.

- StoryCorps: Online archive of thousands of personal narratives (in audio form). Collections of particular interest include StoryCorps Griot (documenting African American stories), the StoryCorps Justice Project (documenting the experiences of BIYOC in the criminal justice system), and the Historias collection (documenting the stories of Latinx people in the United States). StoryCorps is particularly excellent for those interested in modern events and issues.

Review

Review

Race and racism have continued to impact the lives and livelihoods of Americans in the decades since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. Explore the resources below, which dive into the many modern examples of how the racial history of the United States continues to impact our present:

- The Zinn Education Project: Teaching People’s History in the Post-Civil Rights Era, 1975-2000. Includes information and lesson plans about topics such as COINTELPRO (the FBI’s campaign to discredit the Black Freedom Movement), race relations during the Clinton presidency, and the Black Panther party.

- The Zinn Education Project: Teaching People’s History, 2001 – Present. Includes information and lesson plans about topics including the impact of climate change on Indigenous communities, racial inequality related to disaster responses, and the racialized response to terrorism.

- Learning for Justice history lessons: Learning for Justice (formerly known as Teaching Tolerance) has published a broad collection of lesson plans and related materials relevant to the history of race and racism, including modern history. Lesson topics that relate to recent history include mass incarceration and racialized social control, Mexican American labor in the United States, and contemporary civil rights movements.

- Facing History: Race in US History. This site links to nearly 600 resources designed to help educators learn and teach about the history of race in the United States, including modern history. Resources include lesson and unit plans, videos, blogs, images, handouts, audio, and more. Resources that relate to recent history include a unit plan on digital literacy in the context of Ferguson, a lesson on social media protests, and a lesson on the power of images to shape our understanding of current events. Many of these lessons explicitly focus on information literacy content, making them especially valuable for librarians.

Update: Race and CoVID-19

Update: Race and CoVID-19

In the early months of 2020, the United States, along with most of the globe, experienced its first cases of a novel coronavirus infection, COVID-19. As of this update (August 2021), the virus continues to be a major threat worldwide, with the United States currently leading the world in both infections and deaths (source). In response to the virus, most businesses, schools, and other gathering places were closed in mid-March 2020. While multiple vaccines for the virus are now readily available in the U.S., as of this update only half of the U.S. population is fully vaccinated, and the Delta variant is surging.

Alarmingly, the impacts of this virus have not been equally felt across racial groups in the U.S. The virus itself may not discriminate, but our responses to it have resulted in a disproportionately high number of infections, deaths, and negative economic impacts for Black, Latinx, and Native American people.

According to CDC data as of June 6, 2020, Black people have died from COVID-19 at roughly the same rate as white people more than a decade older, and these disparities are largest for middle-aged patients. For example, among patients age 35-44, the COVID-19 death rate for Black patients is ten times that of white patients, and the death rate for Latinx patients is eight times that of white patients (source). The overall rates of infection, hospitalization, and deaths for various racial groups in the U.S. is shown in the table below.

Table 1. Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity. Updated July 16, 2021. Source.

BIPOC are also experiencing greater economic impacts from the virus than whites. In part this relates to the racial wealth gap discussed in Module 1B, which means that Black, Brown, and Native families have a much shakier financial safety net to see them through periods of COVID-related unemployment. But Black and Latinx workers have also suffered greater job and income losses due to the virus, with 61% of Latinx households and 44% of Black households experiencing a job or wage loss due to the pandemic, compared to 38% of white households. Minority-owned businesses were largely shut out of the initial business relief programs funded by the federal government due to bank-imposed rules that prioritized applications from existing customers and delayed those from sole proprietorships (which are disproportionately Black-owned). From just February to April 2020, COVID-19 resulted in a 40% decline in the number of Black business owners in the United States.Why? One reason is that Black and Brown workers are overrepresented in high-risk occupations. One report found that 37.7% of Black workers are employed in essential industries, compared to 26.9% of whites. Black workers are also 40% more likely than whites to work in hospitals. Black and Latinx workers are also much less likely than white workers to have the option to work from home, with just 16.2% of Latinx and 19.7% of Black workers reporting telework as an option, compared to 29.9% of white workers. Early data also show that geography matters: urban areas initially hit hardest by the virus contain higher numbers of BIPOC, Black and Brown people tend to live in higher-density housing compared to white people, and preliminary data show that testing sites have been disproportionately located in predominantly white neighborhoods. Taken together, these numbers show that racism – not race – is a huge risk factor for COVID-19.

It will be many months, if not years, until we fully understand the impact of COVID-19 on our racial history. But as you consume news of the virus, keep racial equity considerations at the forefront. Articles and reports that address the racial inequities surrounding COVID-19 include:

- What Do Coronavirus Racial Disparities Look Like State By State? by Maria Godoy and Daniel Wood for NPR

- White Supremacy is the Pre-existing Condition, by Darrick Hamilton, Dedrick Asante-Muhammad, Chuck Collins, and Omar Ocampo (report for inequality.org)

- Race gaps in COVID-19 deaths are even bigger than they appear, by Tiffany Ford, Sarah Reber, and Richard V. Reeves for the Brookings Institution

- Why Racism, Not Race, Is a Risk Factor for Dying of COVID-19, by Claudia Wallis for Scientific American

- How Black-Owned Businesses were Shut Out of Coronavirus Aid, by Alana Abramson for Time

- Black Businesses Left Behind in Covid-19 Relief, by Andre Perry and Natalie Hopkinson for CityLab

- Study: Covid-19 lockdowns hit black-owned small businesses the hardest, by Aaron Ross Coleman for Vox

- Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race / Ethnicity from the CDC

- The Color of Coronavirus: COVID-19 Deaths by Race and Ethnicity in the U.S. from the APM Research Lab

But Wait!

But Wait!

In this section, we address common questions and concerns related to the material presented in each module. You may have these questions yourself, or someone you’re sharing this information with might raise them. We recommend that for each question below, you spend a few minutes thinking about your own response before clicking the arrow to the left of the question to see our response.

Doesn't this version of history simply represent another biased account of the past?If all this stuff happened, why didn't I learn about it in school?

This history is so different from what is typically taught in schools. What are some small steps we can take to start changing this narrative?

References

Erikson, K. T. (1966). Wayward puritans. New York: Wiley.

Loewen, J. (2007). Lies my teacher told me (10th Anniversary Ed.). New York: The New Press.

| Go Back: Module 1b: Introduction | You Are Here: Module 2: History of Race and Racism | Next: Module 3: Defining Race and Racism |